“Magic leads us to exhilaration and ecstasy; to wisdom and understanding; to transform ourselves and the world in which we participate. Through Magic, we can come to explore the possibilities of freedom.”

-Phil Hine (Condensed Chaos, 1995).Contents show

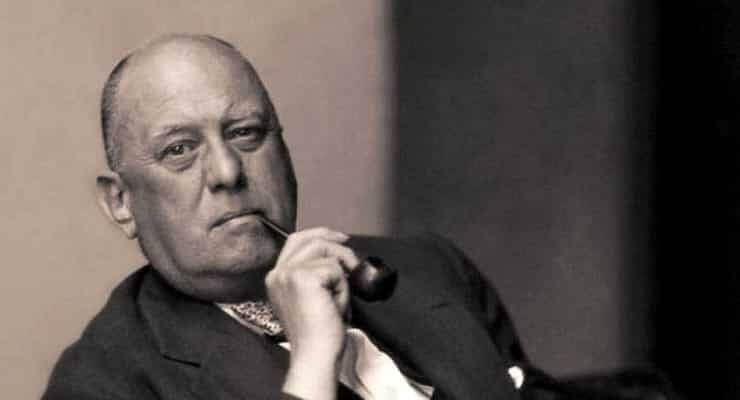

Much of the controversy surrounding Aleister Crowley concerns the use of magic ritual techniques and the cosmology that supported these practices. The cultural context of the time in question warrants attention and the context that Crowley developed and his more personal views on Magic. Suppose the spectrum of influences and his activities’ purposes are explored in their specific sense.

In that case, some of his acts and ideas can be interpreted more sympathetically.

However, my intention is not to offer a rationale for any of Crowley’s more famous deeds (real or imagined), but simply to present a reasonable and balanced evaluation of his extraordinary contributions to contemporary Western culture, especially in the realms of spirituality, sexuality, and occultism. The word religion does not contain an intrinsic sense that lends itself to universal application.

These terms are used as general definitions that can be useful analytical methods when looking at elements of complex ritual practices and cosmologies that tend to have a certain family resemblance. Crowley undoubtedly had a more profound influence on how modern Magic is imagined, portrayed, and performed than any other figure of the twentieth century.

How Magic Turned Magick?

He also gives us a distinct spelling of the word Magic. This spelling was used by Crowley to differentiate his practices from ‘stage magic’ and ‘Magic,’ which attracted ‘dilettanti’ and ‘eccentrics’ who tried to escape from reality.’

His own working concept of Magic was this: ‘Technology and the magick of causing change to occur following Will.’9Always aiming for tangible results, he used ancient and modern techniques, sacred and profane.

This approach led to experimentation that far surpassed the previous limits of his already broad personal boundaries and carnal preoccupations.

Aleister Crowley’s bisexuality

Crowley is perhaps best known for two phrases that have been grossly misinterpreted by those who have never studied the passages in their contexts: ‘Do As You Will;’ and Every man and woman is a star.’ By the turn of the century, Crowley was undisputedly bisexual.

He also used psychotropic drugs and explored Eastern esoteric traditions such as Hindu Tantrism, Yoga, Buddhism, and Taoism. When considering the resurgence of interest in Crowley’s life and legend in the 1960s, his revived position as a counter-cultural figure should come as no surprise.

Let’s answer some of the most basic questions about Aleister Crowley.

- Who was Aleister Crowley?

- What was he doing?

- Who did it influence?

- What is the significance of his work and his image?

Who is Aleister Crowley?

Edward Alexander Crowley (1875-1947) is born in Warwickshire, England. As the son of a Plymouth Brethren preacher and heir to a prosperous family-owned business, Crowley was the product of the upper-middle-class Christian upbringing in Victorian England.

Early on, he was very curious and bold in nature. His mother had already referred to him as the “Beast” when he was thirteen years old; this happened after Crowley had been caught having sex with one of the housemaids. He later attended Cambridge University, a member of the Chess Club, the Freethinkt Society, and the Debate Team.

He was also highly inspired by James Frazer’s The Golden Bough, the work of the “Cambridge Ritualists” (Frances Cornford, Jane Harrison, Gilbert Murray), and Egyptologist Margaret Murray. Crowley had learned Latin and Greek before he attended university.

He also changed his first name to Aleister (Alexander’s Gaelic name variant) because he felt that his given name did not suit him properly.13After receiving his inheritance, Crowley dropped out and left Cambridge without receiving a degree.

The beginning of the journey

“Spiritualism” (communication with the dead and other supernatural beings through seances) had become popular in England and France. As previously noted, an occult revival was taking place in England. While the Theosophical Society was founded in the year of Crowley’s birth (the fact that Crowley saw it as significant), the Golden Dawn Hermetic Order opened its first temple in 1888.

Magic rituals, secrecy, initiation ceremonies, ancient Egyptian and Greek imagery seemed more appealing to Crowley than the Theosophists’ methods.

Simultaneously, Crowley was strongly influenced by Indian and Chinese philosophy and imagery, as were the Theosophists.14 It should be noted that many esoteric groups were founded during this time due to the growing popularity of forms of spirituality and imagery.

In referring to this time, Alison Butler points out that the Order of the Golden Dawn stood out for its focus on ceremonial Magic in the 14th Ghostly realm of the Spiritualists and the Mysticism Mythology of the Theosophists.

Esoteric Science

It was an esoteric culture for magicians to practice.15 This has been a persistent cultural characteristic in London for much of Crowley’s lifetime. And because of his new riches, Crowley was able to completely pursue his desires, even to the point that he traveled to exotic locations to have first-hand contact with practitioners of various mystical religious methodologies.

To evaluate his groundbreaking achievements, a basic understanding of the cultural context from which Crowley arose is required. First of all, this was the Victorian era, which today is considered a period of major sexual repression.

There was, however, a Romantic undercurrent that created enticing reinterpretations of the “virtues” of hedonistic sinfulness as evidenced by Oscar Wilde’s promotion of “New Hellenism” and his admonition to be yourself.

Likewise, Aubrey Beardsley’s Greek God’s performances, Pan, inspired those who wished to step beyond the traditional Christian moral structure in the search for amorality.

Aleister Crowley and Feminism

Feminism and decadence have been connected by an atmosphere of oppressive sexual politics and a shared attraction to mystic groups such as the Theosophical Society and the Golden Dawn Hermetic Order.

According to Alex Owens, “Occultism itself was bound up with a spiritualized vision of social change that called for those ideals of regeneration and self-fulfillment that were deeply appealing to the feminists of the period, and offered a new’ religiosity capable of surpassing the traditional Victorian association of femininity with domestic spirituality.”

Although Crowley, on the basis of some of his own remarks, can often be regarded as a mischievous woman, the role of women in the orders to which he belonged or was founded was by no means negligible. Romantic ideas of oriental “mysticism” were also woven into the fabric of English colonial culture.

The possibility of embracing “exotic” religious practices became appealing to those who wished to escape the grasp of English colonial culture. This led several mystic organizations to begin providing access to the so-called hidden knowledge of the East.

This also led to an increase in interest in the “paganism” of Ancient Greece, Rome, and the British Isles, which some groups considered appealing due to a more local cultural relation. Crowley gradually blended such disparate elements as

- I-Ching,

- Kabbalah,

- Gnosticism,

- Hindu Tantra,

- Buddhism,

- Rosicrucianism,

- Egyptian mythology,

- and the Greco-Roman Pantheon

As the basis of his own religion.

Among the many esoteric organizations that existed in England at the end of the nineteenth century, the Golden Dawn Hermetic Order was exceptional because of its “emphasis on ceremonial magic.”

Famous members of the Golden Dawn Hermetic Order secret society

The group’s membership included notables such as Mina Bergson (the wife of the founder Samuel MacGregor-Mathers and the sister of Henri Bergson), poet W.B. Yeats, Allan Bennett (one of the first Westerners to be ordained a Buddhist monk), Sarah Allgood (stage and film actress), Sax Rohmer (novelist) and Bram Stoker (author of “Dracula”).

After leaving the party, Crowley retained much of his ritual philosophy. He chose to concentrate on what he considered to be a realistic, results-based magick. Thus, he followed and established a 16-day ritual practice that was much more extensive and divisive than other spiritual groups of his time.